Slowing Down to Understanding: Equity vs. Equality

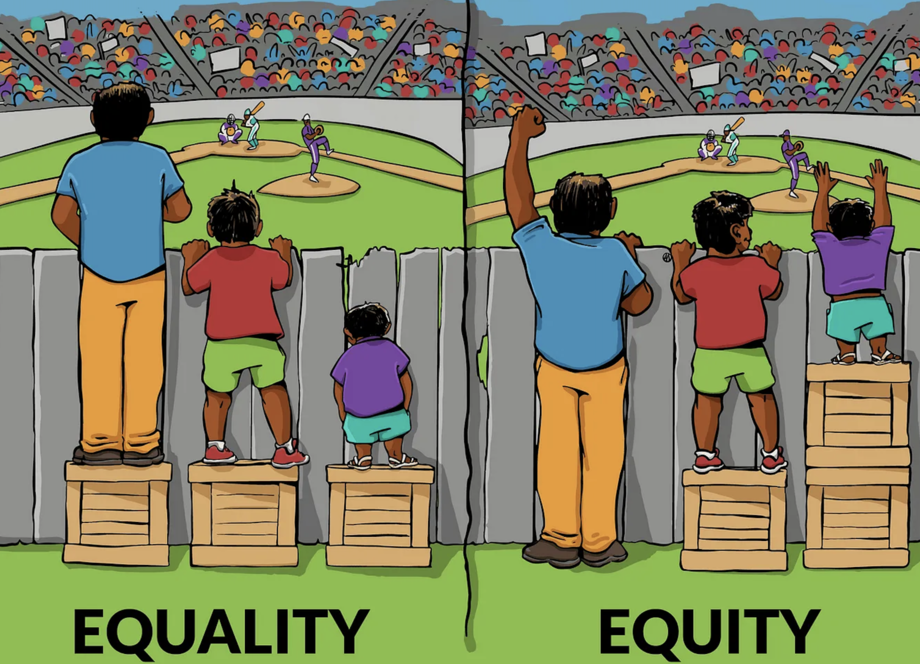

The image is familiar: three children standing behind a fence attempting to watch a baseball game. All are standing on a wooden cube of the same size and height; however, only two can see over the fence. The accompanying image, though, shows that for one child, even when the cube is removed, he can still see over the fence. For another, the cube remains, allowing him to continue seeing over the fence. But for the third child, a second cube has been now added and, finally, he can view the game, along with the others. In education, this image is often accompanied by a description of the difference between equality and equity and, when viewed in its simplicity, is difficult to argue.

As educational systems across North America engage in dialogue about how fairness and justice can be enacted in process and realized in results, necessary focuses include resource redistribution, human resources practice disruption, and removal of barriers. And yet, the primary relationship in our schools is that between teacher and student; it is in this relationship that equity – the type of equity that changes lives – can flourish. Conscious attention needs be on the instructional relationship that centres the students for who they are through a genuine and deep understanding of how each student learns and sees the world.

As you read my words, you are likely nodding your head and asking yourself, “So, what is new? I have heard all of this before.” I would agree with you. That is why I am left wondering why, on one hand, educators collectively nod when the importance of equity is mentioned and then, on the other hand, return to their schools and classrooms, requiring all students to demonstrate their learning in the same way, filling their gradebooks with marks derived from product (even while simultaneously acknowledging the importance of watching and listening to their students), stating that involving their students in co-constructing the description of quality and proficiency takes too long, and/or conflating evaluative feedback with the kind of feedback that can feed learning forward.

Equitable outcomes result from differential treatment. Educators know this; it is in the examination of daily practice, particularly through the lens of assessment and evaluation strategies, that unequivocable differences in the lives our students can be made. Simply put, quality assessment practices are, by their very nature, equitable.

As system leaders, our focus cannot solely be on the design of equitable assessment and evaluation systems in classrooms. The research and writing in this area is overwhelming. Rather, the real work lies in impacting the instructional relationship between student and teacher through leadership that illuminates equity in the assessment and evaluation practices that we, as leaders, use. What that does that mean, practically speaking? Let me unpack this by referencing a longitudinal research study in which I, along with three other researchers, was engaged and whose findings were published in the UK peer reviewed The Curriculum Journal.1

In our classrooms, an aspiration for equity requires discernment; inviting students to determine the best way to show what they know. This does not mean that tests or exams are inherently bad; the creation of a false dichotomy is, at best, intellectually lazy. However, teaching students to consider the method and the timing by which they can best unveil their learning to those who will judge that learning is a means to creating equity; it centres the learner. This does not mean that a curated list of options equates equity. It is in the conversation with the learner that potential pathways can be generated and ‘just right’ decisions made.

This is equally true at the system level. Schools are called to provide evidence of their growth and learning through school planning processes and continuous improvement cycles. But how schools provide evidence of that growth and improvement need not be identical. The research revealed that school leaders, in conversation with system leaders, can describe the best way for them to demonstrate the learning and development of their school, staff, students, and community. And, as system leaders, we are modelling the conversations we know are impactful between student and teacher and that are, by their very nature, equitable.

In our classrooms, an aspiration for equity requires triangulation; valuing evidence from multiple sources over time. Triangulation is a significant pathway to equity. It acknowledges that evidence in a singular form – evidence that privileges a certain way to demonstrate learning – is not equitable. For some students, demonstrating understanding, application, and knowing in the form of a product is appropriate; for others, it is the conversations about the learning or the observation of the learning in process, or a combination thereof, that enables them to best demonstrate progress and growth.

This is equally true at the system level. It is often said that we evaluate that which we value. In the research, system leaders modelled the concept of triangulation by valuing their school leaders’ voices and ways of knowing. They balanced external, lagging data (products) about development and achievement with evidence gathered from observations and conversations. Evidence collected from these triangulated sources was not only acknowledged, but also actively and purposefully curated, examined, analyzed, and communicated. When we do this as system leaders, we are modelling the promise of equity that triangulation offers our students.

In our classrooms, an aspiration for equity requires active participation. Students who are intentionally invited to co-labour and generate with one another and their teachers an understanding of quality and proficiency are more likely to use that knowledge in their own work. This co-construction of criteria is not to be confused with reviewing externally created rubrics, of benefit only to students who are able to infer or who use a perceptual data set to fully understand the meaning of the evaluation criteria. Rather, equity is achieved in the act of slowing down to build that understanding together.

This is equally true at the system level. Policies, statements, and documents that describe what is expected, no matter how clear, can leave some school leaders uncertain. When system leaders roll up their sleeves to collectively unpack and then understand the impact of these policies, statements, and documents on the work that school leaders do, they increase the school leaders’ access to understanding what is expected – no matter the expertise or experience. This is equity. And, along the way, the system leader models the importance of co-constructing definitions of quality and proficiency with learners of all ages.

In our classrooms, an aspiration for equity requires feedback. When feedback feeds learning forward, rather than serving to evaluate it, power dynamics are altered. Equity is ensured because opportunities for refinement, that may have heretofore remained unseen, are unveiled. The learner – the individual – is centred. When that feedback is coupled with an opportunity to revise understanding, learning explodes with possibility and promise.

This is equally true at the system level. When system and school leaders are in the work, are in the learning, together, external, or more traditional measures can be set aside; powerful ‘just-in-time’ data is leveraged to provide frequent feedback. There is no need to wait until the end. Again, power dynamics are altered; system leaders are viewed as walking alongside, rather than evaluators from afar. And when power dynamics shift, equity is enhanced. The research findings showed that when system leaders implicate themselves and increase the feedback (not evaluation) they provide, a commensurate increase in quality feedback across the organization occurs.

Quality assessment practices powerfully amplify equity in our classrooms. If relegated to classrooms only, the research shows system leaders may, unwittingly, ignore a compelling element of their leadership practice: the ability to enhance equity through the alignment gained when modelling is a robust leadership skill.

Sandra Herbst is the Superintendent/CEO of River East Transcona School Division

SIDEBAR

Reference:

- Davies, A., Busick, K., Herbst, S. & Sherman, A. (2014) System leaders using assessment for learning as both the change and the change process: Developing theory from practice. The Curriculum Journal, Vol. 25(4): 567-592. DOI: 10.1080/09585176.2014.964276.

Leave a Comment